'All’ about Finos en rama

To all our Fino friends:

Here’s a summary of at least some of the things we have learnt about Finos VS Finos en rama …

For more than 15 years, TSA revolutionised (including bringing the whole thing back from the brink of extinction) the consumption of Finos in Australia, by aggressively pursuing a freshness program:

ship it fresh

ship it often

sell it out quickly

repeat.

We even had a buy-back scheme in place, if any restaurants and retail stores had ‘stale’ Fino (ie more than 12 months past bottling), we’d swap it out for fresh stock, so that consumers and vendors alike were always confident in the exchange of Fresh Fino. It’s important to note that during this time we were selling what we might somewhat pejoratively call ‘conventional’ Finos – those that were technically filtered (probably tighter than half a micron of filtration). Such Finos are highly stable, but short-lived; they soften and oxidise reasonably quickly and lose the essential zap of the wine.

In the last 7 years, though, a lot has changed.

The ‘revolution’ in Marco de Jerez has brought renewed focus on terroir, and we’ve spent a lot of time (re-) learning the identity/style influences of variants in vientos, Albarizas, Pagos and Parcelas. We’ve learnt how great viticulture can take straight up varietal Palomino from being a hack variety to one of the world’s more interesting whites. Vinos de Pasto - Palominos with some ageing, but short of the age and strength stipulations which determine Finos, have been re-introduced to the market.

And, there have been massive changes in the realm of Finos themselves.

Firstly, lots of historically-styled Finos with great viticulture and an extraordinary degree of terroir complexity have been re-introduced. Some of these are statically-aged (vintage, single-bota bottlings) rather than solera-blended. These days, some arrive at 15% abv (along with at least 2 years of biological ageing, the legal requirement for Finos) entirely with natural alcohol, thanks to a little asoleo (sun-drying), since we repealed the corrupt law from 1969 which stipulated fortification.

Fino is simply the most complex, conceptually/definitionally of all the world’s wine styles.

The last wrinkle of which is the question of filtration.

Since 2016, the TSA crew have been shipping lots of these historical, vineyard-specific “grand cru-equivalent” Finos unfiltered, or ‘en rama’.

Now, there’s no actual rule about what constitutes a Fino en rama (come on, we’re talking about Spain here!). ‘En rama’ doesn’t literally mean unfiltered, it means ‘off the branch’ as in plucked in its natural state. So a Fino en rama is simply as lightly filtered as possible, if not actually unfiltered … Bottling wine after a mere 1, 2 or even as broad as 3 microns of filtration (and in some instances, actually none) radically transforms how our Finos present stylistically.

Let’s take some wisdom from a master.

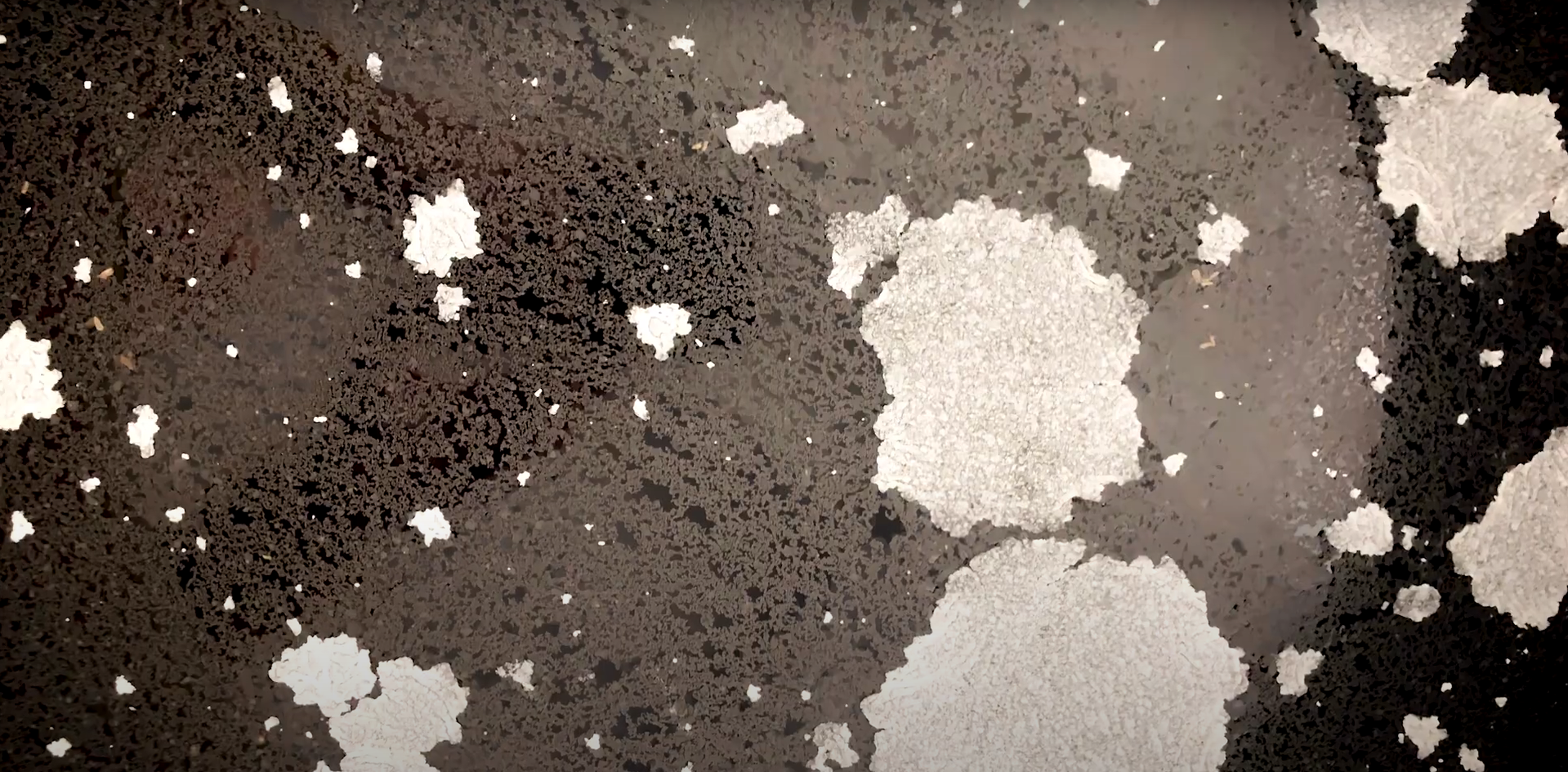

Peter Sisseck’s Viña Corrales is one of el Marco’s leading expressions of single vineyard Finos en rama. Peter says of it, and the rest of the en rama cohort, that “these are wines which come into existence between life and death”. Here he is referring to the flor yeast, which presents in two facets. The living, breathing young fresh Velo de Flor populating the surface of the barrel gives a fresh lively floral yeast character to the Fino, for example the camomile aroma of a lovely Manzanilla. The flor character in its live form has always been high on the list of attributes discussed about Finos. These yeast cells, however, are very short-lived, they die and sediment to the bottom of the barrel. Here over time they concentrate in an entirely different colony called the Cabezuelas. These, Peter refers to as “the historical wisdom of a Soleraje”, many years of spent yeast accumulation adds a remarkable gastronomic bitterness to a Fino … IF, it is not filtered out of the wine.

So, the rub is: technical filtration removes the earthen depth and much of the genuine terroir ID of the Albarizas, and it removes the influence of the Cabezuelas. Filtered Finos are lighter, shallower and more brisk than the earthen, bitter and deep resonance of a Fino en rama. Both are delicious and interesting and gastronomically useful, but they should be considered as dramatically dis-similar wine styles, and not just for gastronomic reasons. They behave dramatically different, especially from a shipper’s point of view. Over time, we think we have over-emphasised the live barrel-top flor. The velo de flor is extremely important - we call it ‘the chisel’: the live yeast and its natural running-mate, aldehyde, ‘cut’ any tendency to puppy fat floppiness from Palomino wines, giving the wines a non-acid edge they need. The flor gives shape.

Here’s what we do, and why …

Filtered Finos are at risk of ‘running flat’ reasonably quickly, and because they are nice and stable, we can ship them, sell them straight away, rotate our stocks and keep on drinking them young and fresh. Finos en rama, however, actually require a period of time in the bottle before they drink at their best. They also require a significant period of time resting in our warehouses to recover and drink at their best after shipping and before being put into the market.

And then!

These wines improve considerably over time – perhaps due to the antiseptic properties of the spent yeast, and also just thanks to their textural depth, great Finos en rama beg to be drunk over several years of steady improvement.

After quite a few years now of handing the 20-odd discrete ‘Crus’ of Fino en rama that we ship, we have arrived at very clear rules for handing these wines before we sell them on to the trade and the public. Finos en rama must be at least 6 months in bottle and they need to have had 3 months of rest in the warehouse post-shipping before we sell them. And, of course we taste them carefully once both these parameters for quality are achieved, and in many instances we’ll choose to hold them for longer. Obviously, this is a very expensive investment in wine quality on our part.

Peter Sisseck’s glorious ‘Viña Corrales’ is a case in point.

Peter bottles this wine just once per year, with a saca (sacar is the verb to take, withdraw) from cask in April, as the wines are starting to wake from winter but before there is too much summer vigour. At this point, TSA has to purchase the wine en primeur, as this is how Peter has always worked with the Pingus wines he is so famous for. So, our current release Viña Corrales Saca 3 was withdrawn from cask in April 2022 and then immediately paid for and shipped, arriving in Australia in July 2022. Theoretically, it met our handling parameters and qualified for release into the market November 1 2022 with more than 6 months of bottle development and more than 3 months of warehouse rest.

As this is a wine we really only want to show at its top, we chose to hold it longer, releasing it in February 2023 after 10 months in bottle and more than 6 months of rest in our warehouse. When you drink your first bottle of Corrales Saca 3, you’ll agree our expense was worth it!